Authored by Rituj Sahu, Director, Protein Transition, India

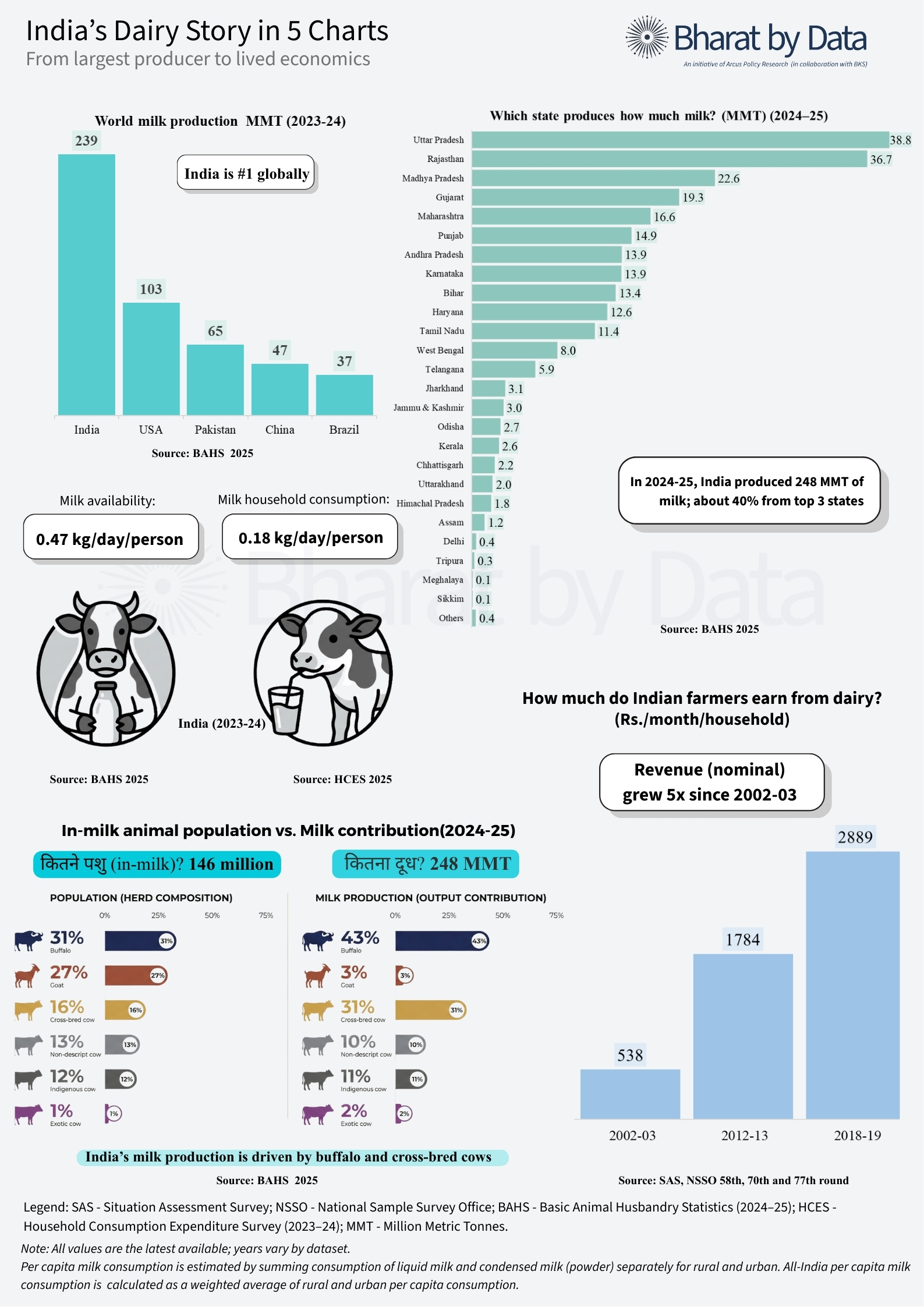

When India speaks about dairy, it’s typically in the language of livelihoods, cooperatives, and rural incomes rather than nutrition policy. Yet, if we look at production data alongside dietary evidence, especially vegetarian diets, it becomes clear that dairy has become not just an income story but also a critical part of how India’s food system delivers protein at scale. It is therefore crucial to protect its value by strengthening aspects of responsible dairy supply. India produces about 248 million tonnes of milk annually, the highest in the world. Nearly 40 percent of this comes from just three states – Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh – supported by an estimated 146 million in-milk animals and millions of smallholder households. These figures are usually cited as markers of livelihood success and income diversification. They are also indicators of how deeply dairy is embedded in daily food systems; and why, as the state expands support through veterinary services, diagnostics, and Farmer Producer Organisations, aligning that support with stronger food safety, animal welfare, and antibiotic-use standards becomes increasingly important.

A recent dietary diversity analysis by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) shows strong regional divergence in dairy consumption. In several northern states, at-home dairy consumption far exceeds recommended national dietary guidelines, while in parts of eastern and northeastern India, it’s a fraction of that amount. More than a piece of cultural trivia, this regional divergence signals that dairy is the default source of quality protein in vegetarian diets and is largely absent from others. It also reflects how connected, or otherwise, different parts of India are to dairy production systems.

How dairy and pulses followed different pathways

For decades, India’s food policy architecture was centred on cereals because rice and wheat were administratively manageable, easy to procure, store, and distribute through the Public Distribution System. Pulses and coarse grains, though nutritionally critical, never fit into this machinery. They remained volatile, harder to stabilise, and peripheral to procurement systems.

The scaling of dairy followed a different pathway. Cooperative structures, daily cash flows, and strong local markets enabled dairy products to expand without depending on centralised procurement. It aligned well with vegetarian food cultures and provided smallholder households with a reliable income. Over time, the differences in how pulses and dairy were supported shaped dietary outcomes in uneven ways. The CEEW analysis shows that pulses today remain under-consumed relative to national dietary guidelines across most states, while dairy consumption is far higher in some regions and far lower in others. In regions where dairy production systems became dense and deeply integrated into rural economies, dairy often ended up contributing more to protein quality in everyday diets. Where such systems did not take root, this pathway is much weaker.

This pattern reflects how food production systems evolved alongside livelihoods, not how nutrition policy was designed. In several southern states, where dairy production has historically been less dominant and dietary patterns rely more heavily on other foods, this dynamic plays out very differently, which is precisely why the CEEW data shows such wide regional variation rather than a single national trend.

Dairy’s dietary role is mediated through value chains

Dairy consumption is not only about liquid milk. National data shows a gap between milk “availability” per person and measured household liquid milk consumption. Much of the dairy product range moves through value chains: curd, paneer, sweets, flavoured beverages, and out-of-home foods. The CEEW study also notes that in dairy-dominant states, higher milk intake is often accompanied by higher sugar consumption through tea and sweets. Dairy’s role in India’s protein system is therefore tied not only to milk but also to processing, informal markets, and food habits that shape overall dietary outcomes.

The industry structure matters

Most of India’s milk still comes from smallholder households owning two to three animals. At the same time, the past decades have seen the growth of medium and larger dairies, along with a complex network of aggregators, cooperatives, processors, and buyers.

Organisations such as Amul (GCMMF), Mother Dairy Fruit & Vegetable Pvt. Ltd., Parag Milk Foods, Schreiber Dynamix Dairies Limited, and global nutrition and food companies source milk through these networks. This structure is both an opportunity and a challenge. Smallholder systems are deeply embedded in rural livelihoods, but they also make it harder to standardise practices without support from intermediaries and large buyers who sit closest to markets.

The Budget is expanding this system governance needs to expand alongside it

The Union Budget 2026–27 places significant emphasis on veterinary colleges, para-vets, diagnostic laboratories, livestock FPOs, and integrated dairy-livestock value chains. This is framed, correctly, as support for rural entrepreneurship and productivity. However, it is also a key opportunity to help strengthen and support responsible dairy: where frontline services improve the welfare of dairy animals to enhance their health and productivity, while reducing the excessive or routine use of antibiotics, supported by more lab testing and protection of dairy safety and quality.

It also creates a clear opportunity to define what responsible dairy should look like as this system expands, not in terms of volume, but in terms of standards. Frontline services can improve animal health and welfare in ways that enhance productivity while reducing excessive or routine antibiotic use, supported by stronger laboratory testing and better protection of dairy safety and quality.

As this system scales, governance questions become unavoidable: reduction of antibiotic use, monitoring of antibiotic resistance and residues, baseline animal health and welfare practices, hygiene in collection and processing, and traceability across supply chains. These are not add-ons; they determine food safety, public trust, productivity outcomes, and the long-term resilience of a sector that many households and consumers depend on daily. There is a clear opportunity, then, to ensure that new public support – whether linked to training, diagnostics, enterprise schemes, or FPO promotion – carries embedded standards as a way to reduce risk, improve quality, and raise the system’s long-term performance.

Seeing the full system

Dairy became central to Indian diets because it fits the political economy of rural incomes and vegetarian food cultures. The result is that, in many regions, dairy materially shapes the protein quality of diets, while in others it plays a much smaller role. Recognising this is not about elevating dairy above pulses or other protein sources. It is about acknowledging dairy’s real footprint where it exists, and ensuring that this system is governed with the same seriousness as the diets it quietly sustains.